A sema in Ancient Greece meant a sign, or symbol. It also had another meaning: a hero’s tomb. We see a connection between these two meanings in The Iliad when Nestor is explaining chariot racing to his young son Antilokhos. However, first we will examine the importance of chariot racing to the Greeks.

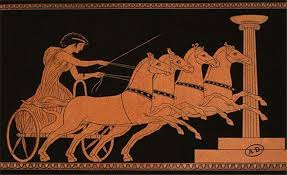

After Patroklos dies in the Iliad, his pshuke (spirit) visits Achilles in a dream. He tells Achilles to organize a funeral and funeral games for him. Achilles does so and holds a chariot race, which could be very dangerous. The race went in a counter-clockwise circle and the left turn was the hardest part of the race. To achieve a left turn, the driver had to manipulate his hands. His right hand would be impulsive, while his left was restrained. When done in equilibrium, the left turn was completed seamlessly. In the center of the race was usually a monument, like a heroes tomb (Achilles had his chariot race around Patroklos’ tomb). If the left turn was performed incorrectly, the rider may smash into the tomb. Legend has it that if the hero who’s tomb it was wasn’t impressed with the rider, his pshuke would come out and spook the horses.

Every year in Athens, a chariot race was held to celebrate the heroes. Stories tell of two people on the chariot, one driver and one rider. This rider would be dressed in full war armor (breastplate, shield, sword etc.) While the chariot was going at breakneck speed, the rider would jump off the chariot and run to the finish. This was quite the spectacle and drew thousands of people every year. Achilles jumped off his chariot during the race dedicated to Patroklos.

There were many life lessons the Greeks took from the chariot races. The theory of having a balance of impulse and restraint was applied to their daily lives. The greek word for turn terma is the root for words today like term, which can refer to a turning point in one’s life. The left terma in a chariot race was life or death in some cases, and was very symbolic to the Greeks.

When Nestor is explaining all of this to Antilokhos, he says:

“I wil give you this sign (sema) that cannot escape your notice.”

Nestor means that at the most difficult part of the race, the left turn around the sema (hero’s tomb) he will give his son a sema (sign) to help him out.

Chariot races were done all over Greece. The athletes represented the heros in battle. The festivals at which the chariot races were held also performed reenactments of Iliad and Odyssey. To the Greeks, this was a way to give kleos (honor) back to the heroes that helped them.